| |

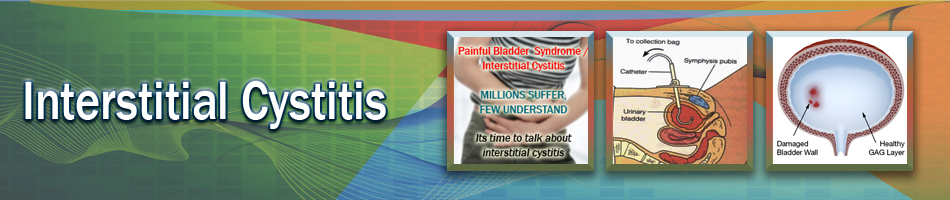

| Interstitial Cystitis (Painful Bladder Syndrome) |

|

|

Interstitial cystitis (IC) is a chronic bladder condition. Its symptoms are pain, pressure, or discomfort that seems to be coming from the bladder and is associated with urinary frequency and/or an urge to urinate. The symptoms range from mild to severe, and intermittent to constant. The more severe cases of IC can have a devastating effect on both sufferers and their loved ones. Many cases are of mild or moderate severity.

In the past, IC was believed to be a rare disease that was very difficult to treat. Now we know that IC affects many women and men. The following information should help you discuss this condition with your urologist and understand what treatments are available.

|

| |

|

What happens under normal conditions? |

|

|

After urine is made in the kidneys, it flows down the ureters into the bladder. The bladder is a hollow, balloon-like organ. Most of the wall of the bladder is made of muscle. As the bladder fills, the muscle relaxes so that the bladder expands and holds urine. During urination, the bladder muscle contracts to squeeze out the urine. The urethra is the tube through which urine passes from the bladder to the outside. The urethra has a muscle, the sphincter, which is completely different from the bladder muscle. The sphincter normally stays closed and makes a seal to keep urine from leaking. During urination, the sphincter opens and lets urine pass.

The bladder and urethra have a specialized lining called the epithelium. The epithelium forms a barrier between the urine and the bladder muscle. The epithelium also helps to keep bacteria from sticking to the bladder, so it helps to prevent bladder infections. |

| |

|

What is interstitial cystitis (IC)? |

|

|

| IC is a chronic bladder condition. Its symptoms may be mild or severe, occasional or constant. It is not an infection, but its symptoms can feel like those of a bladder infection. In women, it is often associated with pain upon intercourse. Interstitial cystitis is also referred to as bladder pain syndrome (BPS) and can be associated with irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, and other pain syndromes. |

| |

|

What are some risk factors for IC? |

|

|

There are no specific behaviors or exposures (such as smoking) known to increase a person's risk for getting IC. The tendency to get IC may be influenced by a person's genes, and so having a blood relative with IC may increase the risk of getting IC yourself. About 80 percent of people diagnosed with IC are women, which suggests that being female may increase the risk of getting IC. However, the difference in rates of IC for men vs. women may not really be as high as we think, because some men diagnosed with "prostatitis" or similar conditions with different labels may really have IC. |

| |

|

How many people in the United States have IC? |

|

|

It is estimated that 3.3 million women and 1.6 million men in the U.S. suffer from some form of IC..

|

| |

|

What causes IC? |

|

|

The causes of IC are being studied in medical centers around the world. Many researchers believe that IC is caused by one or more of the following: (1) a defect in the bladder epithelium that allows irritating substances in the urine to penetrate into the bladder; (2) a specific type of inflammatory cell (mast cell) releasing histamine and other chemicals that promote IC symptoms in the bladder; (3) there is something in the urine that damages the bladder; (4) the nerves that carry bladder sensations are changed, so pain is now caused by events that are not normally painful (such as bladder filling); and/or (5) the body's immune system attacks the bladder, similar to other autoimmune conditions. It is likely that different processes occur in different groups of IC patients. It also is likely that these different processes may affect each other (for example, a defect in the bladder epithelium may promote inflammation and stimulate mast cells). Recent research shows that IC patients may have a substance in the urine that inhibits the growth of cells in the bladder epithelium. Therefore, some people may be predisposed to get IC after an injury to the bladder such as an infection. |

| |

|

What are the symptoms of IC? |

|

|

The symptoms of IC vary for different patients. If you have IC, you may have urinary frequency/urgency or pain, pressure, discomfort perceived to be from the bladder or all of these symptoms.

Frequency is the need to urinate more often than normal. Normally, the average person urinates no more than seven times a day, and does not have to get up at night to use the bathroom. An IC patient often has to urinate frequently both day and night. As frequency becomes more severe, it leads to urgency. Urgency to urinate is a common IC symptom. Some patients feel a constant urge that never goes away, even right after urinating. While others with IC urinate often, they do not necessarily feel the urge to go all the time.

IC patients may have bladder pain that gets worse as the bladder fills. Some IC patients feel the pain in other areas in addition to the bladder. A person may also feel pain in the urethra, lower abdomen, lower back, or the pelvic or perineal area. Women may experience pain in the vulva or the vagina and men may feel the pain in the scrotum, testicle, or penis. The pain may be constant or intermittent.

Many IC patients can identify certain things that make their symptoms worse. For example, some people's symptoms are made worse by certain foods or drinks. Many patients find that symptoms are worse if they have stress (either physical or mental stress). The symptoms may vary with the menstrual cycle. Both men and women with IC can experience sexual difficulties due to this condition; women may have pain during intercourse because the bladder is right in front of the vagina, and men may have painful orgasm or pain the next day.

|

| |

|

How is IC diagnosed? |

|

|

At this time, doctors have different opinions about how to diagnose IC. This is because no test so far has turned out to be completely accurate. All doctors do agree that a medical history, physical exam and urine tests are needed for evaluation. These tests are important to rule out other conditions that might be causing the symptoms. Some doctors believe that IC is present if a patient has IC symptoms and no other cause for those symptoms can be found. Other doctors believe that more tests are necessary to determine whether the patient has IC.

One test that many doctors use is simple office cystoscopy, in which the doctor looks inside the bladder with a cystoscope while the patient is not under anesthesia. This test can rule out other problems such as cancer. Whereas simple cystoscopy can be performed in the doctor's office, a more invasive test can be performed in the operating room. This involves a basic cystoscopic examination followed by a stretching or distention of the bladder by instilling water under pressure. This can reveal cracks in the bladder in more severe cases.

Cystoscopy was once part of the standard IC evaluation, but it is no longer always considered a necessary test for IC because the examination is usually normal. However, during cystoscopy, some IC patients will have small areas of bleeding, or actual ulcers, which the doctor can see through the cystoscope. If a person has symptoms of IC and the cystoscopy shows bleeding or ulcers, the diagnosis is fairly certain. Most people who have IC symptoms do not have these bleeding areas, but they may really have IC after all and may respond to the same treatments. The doctor will often then perform a bladder biopsy, which helps to rule out other bladder diseases. While this procedure is primarily used for testing, some IC patients may experience relief of symptoms afterwards. Some doctors believe that if a person has the typical symptoms of IC, and no other cause for the symptoms is found, then the patient has IC. This is still an area of controversy, and future research may help to resolve it.

Urodynamics evaluation is another test that was once considered to be part of the standard IC evaluation, but is no longer believed to be necessary in all cases. This test involves filling the bladder with water through a small catheter, and measuring bladder pressures as the bladder fills and empties. The usual results with IC are that the bladder has a small capacity and perhaps pain with filling.

Some doctors use a test called the potassium sensitivity test, in which potassium solution and water are placed into the bladder one at a time, and pain/urgency scores are compared. A person who has IC feels more pain/urgency with the potassium solution than with the water, but patients with normal bladders cannot tell the difference between the two solutions. This test is not diagnostic for interstitial cystitis, can be painful, and is not a routine part of the evaluation.

At this time, there is no definite answer about the best way to diagnose IC. However, if a patient has typical symptoms and a negative urine examination showing no infection or blood, then IC should be suspected. |

| |

|

Are there stages of IC? |

|

|

IC is a disease that often starts in a subtle way, sometimes beginning with urinary frequency that the patient may not notice or recognize as a problem. In other cases, the onset is much more dramatic with severe symptoms occurring within days, weeks or months. In many cases, the symptoms become chronic but the disease does not tend to progress after the initial 12 to 18 months. In rare cases, the bladder will become progressively smaller over time to the point where there is almost no capacity to store urine. |

| |

|

How is IC treated? |

|

|

No one knows the cause of IC. Because there are probably several different causes, no single treatment works for everyone, and no treatment is "the best." Treatment must be chosen individually for each patient, based on his or her symptoms. The usual course is to try different treatments (or combinations of treatments) until good symptom relief occurs.

At this time, two treatments are approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat IC. One is oral pentosanpolysulfate. No one knows for certain exactly how it works for IC. Many people think that it builds and restores the protective coating on the bladder epithelium. It may also help by decreasing inflammation or by other actions. The usual dose is 100 mg three times a day. Possible side effects are very uncommon and the most common are nausea, diarrhea and gastric distress. Four percent of people will experience reversible hair loss. It often takes at least three to six months of treatment with oral pentosanpolysulfate before the patient notices a significant improvement in symptoms. It is effective in relieving pain in about 30% of patients.

The other FDA-approved treatment is to place dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) into the bladder through a catheter. This is usually done once a week for six weeks, and some people continue using it as maintenance therapy (though at longer intervals; not every week). No one knows for certain how DMSO helps IC. It has several properties including blocking inflammation, decreasing pain sensation and removing a type of toxin called "free radicals" that can damage tissue. Some doctors combine DMSO with other medications such as heparin (similar to pentosanpolysulfate) or steroids (to decrease inflammation). No studies have tested whether these combinations work better than dimethyl sulfoxide alone. The main side effect is a garlic-like odor that lasts for several hours after using DMSO. For some patients, DMSO can be painful to place into the bladder. This can often be relieved by first placing a local anesthetic into the bladder through a catheter, or by mixing the local anesthetic with the DMSO.

A wide variety of other treatments are used for IC, even though they are not specifically approved by the FDA for this purpose. The most common ones are oral hydroxyzine, oral amitriptyline and instillation of heparin into the bladder through a catheter.

Hydroxyzine is an antihistamine. It is thought that some IC patients have too much histamine in the bladder, and that histamine promotes pain and other symptoms. Therefore, an antihistamine can be helpful in treating IC. The usual dose is 10 to 75 mg in the evening. The main side effect is sedation, but that can actually be a benefit because it helps the patient to sleep better at night and get up to urinate less frequently. The only antihistamines that have been specifically studied for IC are hydroxyzine and (more recently) cimetidine. It is unknown whether other antihistamines will also help treat IC.

Amitriptyline is described as an antidepressant, but it actually has many effects that may improve IC symptoms. It has antihistamine effects, decreases bladder spasms, and slows the nerves that carry pain messages (for that reason, it is used for many types of pain, not just IC). Amitriptyline is widely used for other types of chronic pain such as cancer and nerve damage. The usual dose is 10 to 75 mg in the evening. The most common side effects are sedation, constipation and increased appetite.

Heparin is similar to pentosanpolysulfate and probably helps the bladder by similar mechanisms. Heparin is not absorbed by the stomach and long-term injections can cause osteoporosis (bone thinning), and so it must be placed into the bladder by a catheter. The usual dose is 10,000 to 20,000 units daily or three times a week. Side effects are rare because the heparin remains only in the bladder and does not usually affect the rest of the body.

Many other IC treatments are also used, but less frequently than the ones described. Some patients do not respond to any IC therapy but can still have significant improvement in the quality of life with adequate pain management. Pain management can include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, moderate strength opiates and stronger long-acting opiates in addition to nerve blocks, acupuncture and other non-drug therapies. Professional pain management may often be helpful in more severe cases. |

| |

|

What can be expected after IC treatment? |

|

|

The most important thing to remember is that none of the IC treatments works immediately. It usually takes weeks to months before symptoms improve. Even with successful treatment, the condition may not be "cured;" it is simply "in remission."Most patients need to continue treatment indefinitely, or else the symptoms return. Some patients have flare-ups of symptoms even on treatment. In some patients the symptoms gradually improve and even disappear.

Although most patients will find that their symptoms improve as they are treated for IC, not all patients will become completely symptom-free. Many patients still have to urinate more frequently than normal, or have some degree of persistent discomfort and/or have to avoid certain foods or activities that make symptoms worse.

|

| |

|

Is it possible for IC to recur after successful treatment?

How can recurrences be prevented? |

|

|

It is possible for IC symptoms to recur even if the disease has been in remission for a long time. It is not known what causes recurrences. Also, there is no known way to prevent recurrences for certain. Some things that patients do to try to prevent recurrence include: (1) stay on their medical treatments even after remission; (2) avoid certain foods that may irritate the bladder; and (3) avoid certain activities or stresses that may worsen IC. The specific foods or activities that affect IC are different for different patients, and so each person has to form his/her own individual plan. |

| |

|

| Frequently Asked Questions: |

| |

How does diet affect IC? |

|

|

Most (but not all) people with IC find that certain foods make their symptoms worse. There are four foods that patients most often find irritating to their bladders: citrus fruits, tomatoes, chocolate and coffee. All four of these foods are rich in potassium. Other foods that bother the bladder in many patients are alcoholic beverages, caffeinated beverages, spicy foods and some carbonated beverages. The list of foods that have been reported to affect IC is quite long, but not all foods affect all patients the same way. For this reason, each patient must find out how foods affect his or her own bladder.

The simplest way to find out whether any foods bother your bladder is to try an "elimination diet" for one to two weeks. On an elimination diet, you stop eating all of the foods that could irritate your bladder. IC food lists are available from many sources (www.ichelp.org or www.ic-network.com). If your bladder symptoms improve while you are on the elimination diet, this means that at least one of the foods was irritating your bladder.

The next step is to find out exactly which foods cause bladder problems for you. After one to two weeks on the elimination diet, try eating one food from the IC food list. If this food does not bother your bladder within 24 hours, this food is probably safe and can be added back into your regular diet. The next day, try eating a second food from the list, and so on. In this way, you will add the foods back into your diet one at a time, and your bladder symptoms will tell you if any food causes problems for you. Be sure to add only one new food to your diet each day. If a person eats a banana, strawberries and tomatoes all in the same day, and the IC symptoms get bad that evening, he/she will not know which of the three foods caused the symptom to flare up. |

| |

|

Does stress cause IC? |

|

|

At this time, there is no evidence that stress makes a person get IC in the first place. However, it is well known that if a person has IC, physical or mental stress can make the symptoms worse. |

| |

|

Is IC hereditary? |

|

|

There is some research that indicates that there is a genetic pattern. It is important to discuss the symptoms of IC with the family, especially the females, so that any other affected members can be screened and treated early in the disease process. |

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Endoscopic removal of urinary stones: PCNL, URS, RIRS, CLT |

|

|

Lithotripsy (ESWL) |

|

|

LASERS for stones and Prostate |

|

|

Monopolar and bipolar TURP |

|

|

HOLEP |

|

|

Urodynamics and uroflowmetry |

|

|

Laparoscopic urology surgeries |

|

|

Paediatric urology surgeries |

|

|

Urinary incontinence surgeries |

|

|

Surgeries for genitourinary cancers |

|

|

Reconstructive urology |

|

|

Microsurgeries for infertility and impotence |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|